This story is part of PS Weekly Podcast, collaboration between chalk beat and The Bell. To hear the full audio version of this story, go to recent episodes.

When fourth-grader Elsa Hammerman's favorite food disappeared from her school's lunch menu this spring due to budget cuts, she rushed to write a letter to the head of the New York City School Food Authority.

Her plea, adorned with 13 hand-painted chicken drumsticks, was polite but direct. Bring your roast chicken home to her PS/IS 187 in Washington Heights. It didn't take long for her advocacy to pay off. Within a few weeks, the dish reappeared in her school's cafeteria.

“I was so happy, I felt like I was jumping off my friend's shoulders, and she was like, 'Calm down, calm down,'” Elsa recalled. “Everyone was so excited to see it come back.”

Elsa wasn't the only student to complain about the cuts. Schools Superintendent David Banks said officials ultimately reinstated many of the menu items after the city was forced to remove some of the most popular dishes from the cafeteria due to a $60 million cut. He cited student protests as the reason. But Elsa's letter also earned her school the chance to consider future dishes that could appear in cafeterias in hundreds of schools across the city.

After receiving Elsa's letter, Chris Tricarico, senior executive director of food and nutrition services, invited Elsa's class to the Department of Education's School Lunch Test Kitchen. Each year, approximately 1,500 to 2,000 students across the city come to provide feedback on new menus the city is considering for school cafeterias. This visit is so popular that there is a waiting list for principals.

“We were able to acclimate her,” Tricarico said. “So all of her classes now know that their voices, their interests, and their support for school meals really matter.”

Last month, Elsa and about 20 of her fourth-grade classmates visited the department's test kitchen in Long Island City, Queens, and made egg and cheese sandwiches, a cheesy pasta dish called manicotti, hummus and barbecue chicken sliders.

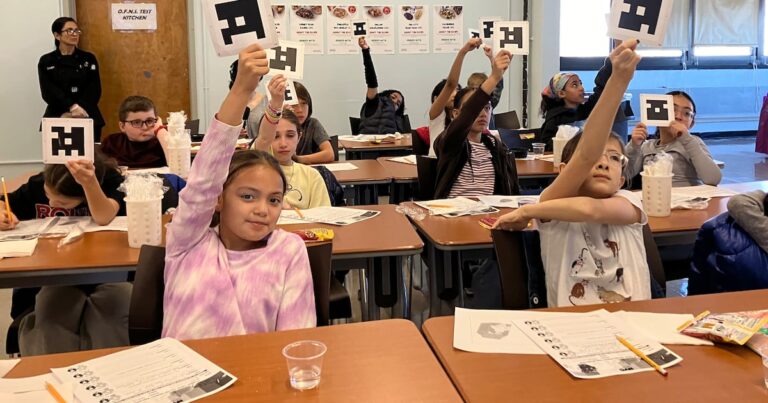

Students gathered in a mock classroom in a warehouse-style building sampled each product while sitting at rows of desks. They sampled the food without talking so they could develop their opinions without influencing each other. Using fancy barcode-like cards called prickers, they indicated their overall rating. If they hold up the card with the correct side up, it means they approve of what they just ate.

Typically, each food item is sampled by approximately 200 students and requires approximately 75% approval before being added to the school cafeteria.

Chantal Hewlett, the taste test supervisor, stood at the front of the room and scanned all the codes at once with her cell phone, instantly tallying the number of students who liked the dish. Students then shared more detailed feedback on the worksheet and verbally during group discussion.

“If you don't like something, that's okay. Just let us know right away so we can fix it,” Mr. Hewlett explained to the fourth graders. “We have received your comment and will share it with the company.”

Elsa and her classmates didn't hesitate to share their honest opinions about food. The first dish was a dinner roll stuffed with egg and melted cheese and was almost a winner.

One student said in unison, “I really like this meal.'' “I always get a headache when I eat eggs, but I liked the way they were cooked. [it] I hated having a headache. ”

18 out of 22 student testers gave the eggs favorable reviews.

The manicotti (tubular pasta stuffed with ricotta and sprinkled with tomato sauce and parmesan) was a different story. Of the 21 students who tried it, 11 moved the barcode to the side and gave a thumbs up.

One student said, “There was so much cheese that when I tried to eat it, it stuck to my plate, so I didn't like it.'' The ricotta was a major drawback for many student critics.

School food officials emphasized that even the harshest student criticism is important. After all, if there's food left on a cafeteria tray that a student doesn't like, they're going to throw it in the trash. And student feedback is even more important as city officials experiment with more culturally diverse menus and a wider range of vegetarian options on “Meatless Mondays” and “Plant-Based Fridays.”

After the test kitchen visit, the fourth graders reflected on their experience. One of the students, Athena, said she usually relies on food sent from home.

“I think school lunches are better now,” she said.

Another classmate, Benson, said Elsa's letter might inspire her to pursue her favorite cuisine.

“I really appreciate the letter she wrote. And maybe I'll write one too,” Benson said.

What does it say?

“To add fried chicken to the menu,” Benson replied.

To hear the details of Elsa's visit to the school lunch kitchen, Listen to the latest episode of PS Weekly.

Eva Stryker Robbins is a senior at Beacon High School in Manhattan and an intern at The Bell.

Alex Zimmerman is a reporter for Chalkbeat New York, covering New York City public schools. To contact Alex, azimmerman@chalkbeat.org.