Few would know that an unassuming five-story apartment building on West 48th Street across from Clinton Community Gardens holds a significant place in New York City LGBTQ history. Once home to queer pioneers and outspoken advocates for transgender and gender non-conforming people, the apartment building's halls were filled with queer joy and laughter from at least 1972 to 1975.

Lee G. Brewster (1943-2000), whom writer Abby Seipen described in a magazine article as “a social activist, rebel, martyr and businessman,” may not be a name that immediately springs to most people's minds when thinking about the queer movement of the 20th century.

But the activist and entrepreneur, who lived at 445 W 48th Street (across from 9th/10th Ave.) in the early to mid-1970s, was a drug addict. She also ran Mardi Gras, a cinematic-style clothing boutique for drag queens and gender variant people, for nearly 30 years. Toothy, Birdcage and Thank you so much, Wong Foo, Julie Newmar.

Brewster has called himself a “drag queen” and a “cross-dresser” at various times in his life. In interviews and publications, he is referred to as a gay man and uses he/him pronouns.

Born in Honaker, Virginia, to a coal miner's father, and raised in West Virginia, Brewster (the G stands for Greer) left home at 17 to work for the FBI in Washington, D.C. Just a year later, he was outed as gay, arrested and fired, he recalled in a 1994 interview with The TV-TS Tapestry magazine.. He then left for New York and soon joined the Mattachone Society, an early gay organization.

At the time, Brewster, who frequently cross-dressed, hosted cross-dressing balls to raise money for the Mattachone Society—ironically, the relatively conservative organization for which he worked did not approve of cross-dressing or any form of transgender expression.

“They were trying to present themselves as more gender-normative in order to be accepted by straight society,” explains historian Jeffrey Iovanone, who studied Brewster's life and legacy for the New York City LGBT Heritage Project. One of the association's main goals was to get gay people hired in the federal government and other workplaces.

Brewster's balls were such a success that upon his death, The New York Times reported in 1973 that “his final ball was attended by the real Jacqueline Susann, Carol Channing and Shirley MacLaine.”

Due to the association's views, Brewster eventually left and founded her own group, the Queens Liberation Front, with fellow drag queens Bunny Eisenhower, Bebe Scarpe, Chris Moore, and Vicki West. Their initial goal was to allow people of different genders and those who chose to dress in drag to meet in public. By 1971, the group led a legal campaign that succeeded in overturning a city ordinance banning cross-dressing. In the 1970s, the group had offices in a now-demolished building at 445 10th Avenue (at the intersection of West 34th and 35th Streets).

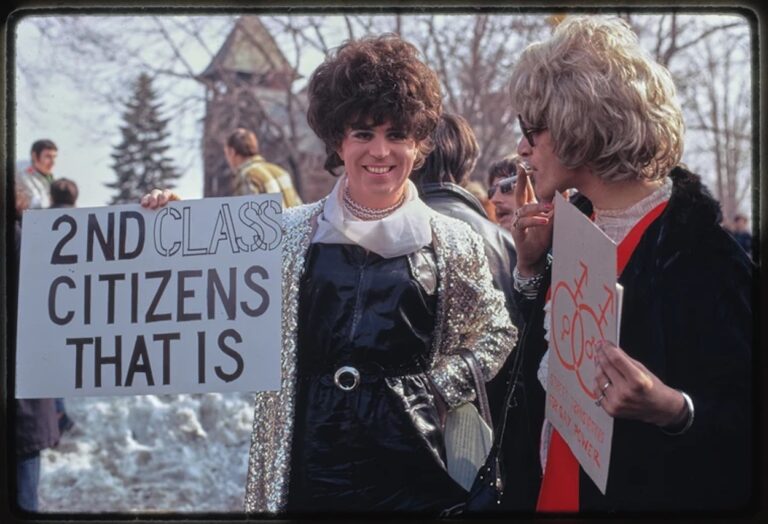

Members of the Queens Liberation Front, including Brewster, took part in the Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade in 1970, the year after the Stonewall riots. In 1971, the Queens Liberation Front took part in a protest in Albany calling for the legalization of cross-dressing. Here, Brewster stands next to trans activist Sylvia Rivera, founder of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR).

Brewster's Drugs first issue magazine The magazine was published in 1971, according to the Digital Transgender Archive, which has preserved and digitized copies of the publication. Originally conceived as an “art magazine,” throughout its run it has featured photos from drag balls, interviews with prominent drag queens, news about the queer community, and practical information about taking hormones and transitioning.

Iovanon said Brewster's views, expressed through the magazine, “present a broader and more fluid view of gender that I believe is prescient of how we understand transgender and non-binary identities today.”

An anonymous editorial in the first edition read: “Now, straight or gay, part-time or full-time drag queens, it's time for us to step down from our thrones as 'queens' and step out into the 'regular' public and let it be known that we are really human beings, with real feelings.”

Brewster worked hard in his early days. In 1969, he started a mail-order business for cross-dressers. He sold his wares from his apartment at first, then opened Lee's Mardi Gras Boutique in the mid-70s, which he operated until his death. His first two stores were located in Hell's Kitchen at 565 10th Avenue (now the site of the luxury apartment building The Victory) and 400 West 42nd Street (now the site of the Pod Times Square Hotel), before moving in 1989 to 400 West 14th Street (above the Gucci store in the modern day Meatpacking District). The boutique was always located on the second floor for the safety of its customers, who had to ring a bell to go upstairs.

Brewster left the gay liberation movement early on, citing what he saw as stigmatization of drag queens and gender non-conforming people at the time, and at the last march he attended he held a sign that read, “I'm just a stereotype, but I'm also proud of it,” echoing comments he made in a 1995 interview broadcast around the world.

“That year I sat there and watched people in the gay movement ask the press not to interview me about drag,” he said. “And you know how hard that was? So I basically left the movement because it hurt me. Gay people were telling me I wasn't good enough for them. I was being shunned by crossdressers, straight crossdressers. … It was like I was being hit over the head and I couldn't take it anymore. It's hard to keep fighting constantly.”

Brewster was fascinated by Mardi Gras — the one day a year in pre-1970s New Orleans when people considered male by society were allowed to dress as women — and he led a week-long excursion each year to a Southern city, during which he dressed as a woman.

“We always went out in large numbers on Mardi Gras Tuesday, but we would arrive on the Thursday before and dress up all week,” Bebe Scarpe explained in a 2007 interview with Transgender Tapestry. “It was pretty daring at the time, because cross-dressing was illegal except on Mardi Gras day, Fat Tuesday, until 1970, but we didn't let that stop us. On Thursday night we walked into a restaurant and Leigh was at the front of a group that was attractive and well-dressed. Other diners were gasping, sticking their forks in the air, at the sight of people dressed as women before the official Mardi Gras.”

Scarpe met Brewster in 1971 and became editor-in-chief of Drag., The Queens Liberation Front explained that they had held a party at Brewster's apartment rather than an official meeting, because “Lee, without any thought or ill will, had registered all of his apartments, so that his addresses were publicly available.”

“Lee's parties were different,” she recalls. “They were really about creating a place where people could put on make-up and high heels and chat and mingle, just like we do now. One of the magazine's strengths was the choice of images that portrayed parties as fun and sociable places, rather than overtly sexy or scary.”

In an interview with the NYC Transoral History Project, Sandra Messick, a nurse who visited Brewster's boutique, recalled, “Lee was truly a Southern gentleman. I use the word gentleman because Lee carried himself as a man most of the time. Lee loved high drag and he went all out with gowns and sequins and all that.”

Shannon Harrington, a “wig master, hair chaser and makeup artist” who worked at Mardi Gras Boutique from the 1980s until it closed, recalled that Brewster would take her and other employees out to dinner to “fancy restaurants that we normally wouldn't be able to afford.”

She enjoyed hearing stories from Brewster's past. “He was also a very generous person,” she said. “That's what made Lee so special.” For example, he was the first employer to offer her full health insurance.

Brewster died of cancer on May 24, 2000. As Harrington recalls, boutique rents were skyrocketing at the time: “They went from $5,000 a month to $10,000 to $15,000, then they were asking $20,000,” she says. “So they were probably asking about the same rent then as they are now.” She believes the stress associated with the diagnosis may have been part of what led to his sudden death.

Brewster's story may not be as well known today, Iovannon said, because “I think when we think about LGBTQ history, we default to looking at activists.”

“Activism is sexy, it's visual,” he says. “Being an entrepreneur and running a boutique is less visible. [it] It's been around for decades and has clearly played a vital role for the transgender community in and around New York City.”

This is just a brief introduction to the life and legacy of Lee G. Brewster and the LGBTQ history of Hell's Kitchen.

If you have personal memories of Brewster, Brewster’s boutiques, or queer life in the neighborhood in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, we’d love to hear from you. Contact us at dashiell@w42st.com.