Fast-moving flames destroyed the heart of the Lone Star State's cattle country, scorching about 2,000 square miles of grasslands that support tens of thousands of cattle. Texas Agriculture Secretary Sid Miller said about 3,600 animals have died so far and more will be euthanized because their hooves and udders were burned in the fire. He said it could be years before the grass regrows and the cows return, but the cost of rebuilding fencing, barns and other ranch infrastructure is estimated to be huge, and insurance won't cover it. Said it wasn't covered.

The disaster occurred less than a year after flooding from nearly a year's worth of rain inundated other parts of the Panhandle region. Then, a drought dried up vegetation throughout the region. Experts say this cycle increases the risk of wildfires across the West and Southwest, but some Texas farmers say it's just part of life in the Panhandle.

Jared Blankenship, a rancher and farmer in Hereford, Texas, and regional representative for the Texas Farm Bureau Federation, remembers his grandfather talking about similar changes in weather and fortunes decades ago. he said. In parts of the country where dry conditions are common, fires are always a concern, even though flames don't usually spread very quickly.

“We're going through this unusual year either way, and unfortunately it's like boom or bust,” Blankenship said. “We are getting used to these events on a regular basis.”

It's just a part of the world where “the same thing could happen tomorrow.”

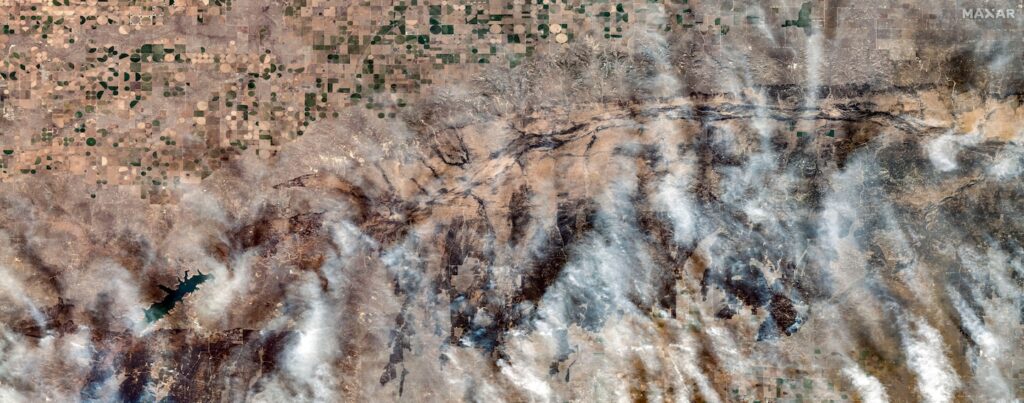

But the fire, already the largest on record in Texas, is expected to grow even more, even as firefighting conditions improve. The Smokehouse Creek Fire had burned 1,059,570 acres and was 37 percent contained as of Tuesday morning, according to the Texas A&M Forest Service. (The Forest Service says improved mapping has made this slightly smaller than previous estimates.)

Miller predicted that if firefighters continue to contain the fire, it could spread to more than 2 million acres by the time it is extinguished, possibly by the end of this week. If that happens, it would be the third-largest wildfire in U.S. history, surpassing even the largest wildfire on record in California and second only to wildfires that occurred in less-developed areas more than 100 years ago.

Char Miller IV, a professor of environmental analysis at Pomona College, said global warming is now intensifying weather “whiplash” cycles like those experienced in the Texas Panhandle, where extreme rainfall can destroy plants. It said it promotes growth and then the plants flare up in extreme heat and drought. The former professor at San Antonio's Trinity College said the fire threat is not just growing in Texas.

“That's as true in California as it is in Texas,” Miller said. “That’s just as true in Arizona as it is in Colorado.”

In the Texas Panhandle, the fire moved across grassy pastures and flames rose 20 to 30 feet high, Sid Miller said. Thousands of miles of fence have been destroyed, he said, costing about $10,000 per mile to install. Additionally, some ranches lost all their cattle, costing about $3,000 per head to replace them. Their burials are also not covered by insurance.

Other extreme weather conditions were already challenging farmers in the region. Sid Miller said recent cotton crops have failed due to the drought. Hutchinson County also said untimely heavy rains and hail last spring and summer resulted in very few tomatoes in the area and limited the amount of sweet corn some farmers could plant. said Adrian Brockett, manager of the farmers market.

“Some of them may fall,” Sid Miller said. “That's pretty hard to overcome.”

Many ranchers are now having to consider how to move forward. Blankenship said farmers across the state and region are sharing hay bales to make sure their remaining cattle have something to eat, but many of their animals will have to be relocated indefinitely. They say it won't happen.

Sid Miller said the Panhandle region is home to about 85% of Texas' 11 million head of cattle, but ranchers' losses are not expected to have a widespread impact on beef supply and prices. He said no. Kevin Good, vice president of industry research firm CattleFax, said these cows represent a small portion of all U.S. cattle and could put minimal, if any, upward pressure on beef prices. Ta.

Still, the threat of further fires is expected to continue in the coming months.

In Texas, prairie fire season starts as early as November and typically spikes around March and April, when winds start to pick up, said Carl Flock, a forest ecologist with the Forest Service. In addition to strong winds and persistent grass cover, human-caused ignition is usually required for fires to spread as quickly as they have recently, he said.

For now, winds are relatively calm, with some cold rain or light snow expected across the Panhandle on Friday.

But the strongest winds of the year are usually weeks away. Blankenship said southwest wind gusts of 40 mph are common in March and April. There are concerns not only about further fires, but also about wind erosion of already burnt areas. This condition will continue until heavy rains occur and new grass takes root.

“There's nothing holding the ground up,” Blankenship said.

Sid Miller said as aid flows into the region to help farmers and ranchers rebuild, he encourages them to take care of themselves. Like other states, Texas has a dedicated hotline, the AgriStress Helpline, staffed by operators specially trained in the perils of farming in these difficult environments. .