Last month, Oscar Hernandez had trouble sleeping. The chef at a Las Vegas casino restaurant noticed he couldn't cool down after coming home from a shift.

The air conditioning at his workplace had been out of order for about four months. Hernandez worked eight-hour shifts during the restaurant's brunch service, making eggs, waffles, and fried chicken. He spent hours in front of a sizzling grill, an older model that could only cook at very high temperatures. His spot on the line was usually in the corner, where all the other heat sources in the kitchen seemed to be concentrated: a gas burner, four deep fryers, a waffle iron. Summer hadn't officially started yet, but Las Vegas' May temperatures were already above average, sometimes reaching triple digits. The fans the owner had installed in the kitchen weren't powerful enough to cool the space.

Hernandez, who lives in Nevada and has worked in the restaurant industry for 22 years, is nothing new about sweltering heat, but conditions were becoming unbearable at his Las Vegas Strip restaurant. The kitchen was sometimes too hot, and Hernandez preferred working outside in the heat, where there was at least a breeze. He suffered persistent headaches, and at home, his kids would get irritated over little things.

“The heat in a restaurant is different. It gets to you,” Hernandez said in an interview in Spanish. He knew doctors recommend getting plenty of rest to recover from heatstroke, but now he can't even do that. So he quit.

“I'm the only one in my family who works,” he said, “so I thought I'd find another job where I could work comfortably and hopefully get some sleep.” He then found work at another restaurant.

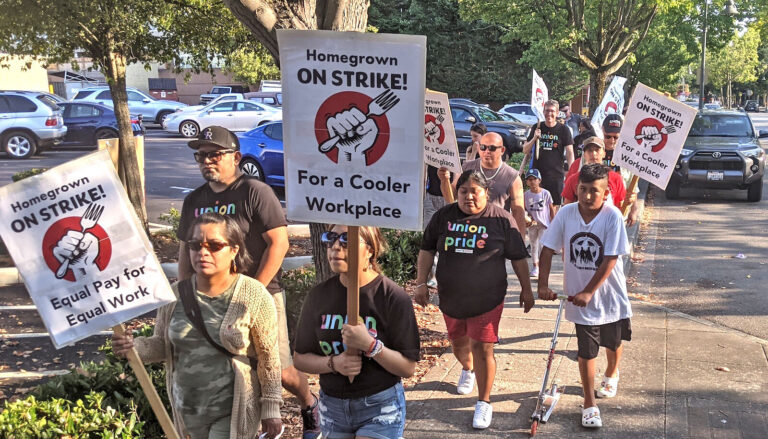

Stories of working while exposed to heat stroke are common in the restaurant and food service industries, where back-of-the-line workers must stand for hours cooking and preparing food next to hot stoves, ovens, fryers, and more. But these workers are also increasingly dealing with additional sources of heat exposure outside the kitchen, including record-breaking summer temperatures and heat waves. The combination of indoor and outdoor heat has prompted some workers to unionize and fight for stronger safety measures in the workplace. Employees at a Seattle-based sandwich chain recently secured historic protections against extreme heat in their first union contract. Union organizers expect to see more food service workers band together to negotiate over heat in the coming years.

Of all the climate issues workers face in the workplace, “I think heat is one of the most prevalent issues right now,” said Yana Karmika, a volunteer organizer with the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee, a grassroots movement started in the wake of the pandemic to help workers organize.

Scientists are now all Heat waves become more likely and stronger with climate change, thanks to the relatively new but growing field of “attribution science,” which allows researchers to determine how much a warming planet makes extreme weather more likely. A report released last month found that human-induced climate change increased the number of days of extreme heat by an average of 26 days globally last year.

Food workers have long been on the front lines of worsening global warming: U.S. agricultural workers are inevitably exposed to the elements, but there are no federal regulations regarding heatstroke or safety. Delivery workers also must travel through scorching heat (and other weather events) to make a living, and may not have adequate rest areas throughout the day.

Similarly, restaurant cooks and servers are often exposed to extremely high indoor temperatures, and outdoor temperatures can exacerbate heatstroke in some work environments. Because restaurant work relies on speedy service and kitchens remain open during a global pandemic, employees may be expected to report to work shifts in record heat, putting their own safety and that of their customers at risk.

Jason Flynn, a Chicago-based chef who has worked in restaurants for years, said the fast pace and high pressure of commercial kitchens means workplace injuries are often easy to endure and workers may feel they have no choice but to work while exposed to excessive heat. As a result, “people end up passing out, having strokes or suffering other long-term heat-related problems like blood pressure and heart problems,” he said.

Certain restaurant jobs are disproportionately represented by women and people of color. For example, Hispanics are more likely to be hired as dishwashers and cooks, according to a report from the Economic Policy Institute. Many are immigrants or undocumented, and may fear retaliation or losing their jobs if they speak out about working conditions. “These are people who are already disproportionately affected by climate injustice in their homes and communities,” says Karmica. “And their increased exposure to extreme heat in the workplace is just another facet of how unequal the impacts of the climate crisis are.”

There are several ways that the heat outside can make it worse inside for restaurant workers. Tall windows in restaurants and cafes can let in a lot of heat on sunny days, as is the case at several locations of Homegrown, the Seattle-based sandwich chain that recently unionized and won some heat-relief measures.

Some Homegrown locations are in older buildings that don't have air conditioning, workers say. Most have counter service, with employees taking orders in the same area where they toast bread and prepare sandwiches. “We're in this big old brick building,” says Zane Smith, a Homegrown worker organizer. “It doesn't have much air conditioning, and we have an oven, so the whole building is one big brick oven.”

Smith, a Seattle native, said heat was one of the main issues workers united around when they first began talking about unionizing. Despite working indoors, Homegrown workers say they've felt the effects of Seattle's record-breaking summer heat. The city, which has historically lacked air conditioning, faced record-breaking heat in 2021, with temperatures reaching 108 degrees Fahrenheit and many hospitalized with heatstroke. Attribution scientists said this unprecedented heatwave was made at least 150 times more likely by human-induced climate change.

“It's always hotter inside than outside,” Smith said. “When it's 80 degrees outside it's 85 degrees inside, and when it's 90 degrees outside it's 95 degrees inside.”

Maris Sivirc

In perhaps an industry first, Homegrown workers won language in their union contract in March that would help them do just that. They fought for a clause that would allow them to receive 1.5 times their pay if the temperature in the store reached 82 degrees Fahrenheit and double their pay if it reached 86 degrees. (According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, workplace temperatures that reach 77 degrees can make it unsafe for workers to perform “strenuous work.”)

Emily Minkus, who has worked at Homegrown for nearly six years, said that during negotiations with management, colleagues shared stories of working through heatstroke and illness.

“We've had people pass out, people have had asthma attacks,” Minkus said. “Some people are taking breaks in the walk-in freezers.”

She says these testimonies helped convince management that workers were demanding heating allowances because “it was necessary,” not because “it was ideologically good for the world.”

Homegrown workers are unionized with Unite Here Local 8, which represents about 4,000 hospitality workers in Oregon and Washington. Anita Seth, president of Unite Here Local 8, said the goal of Homegrown's heating allowance provision is to “actually encourage employers to update and improve their heat mitigation systems,” which can include repairing and maintaining air conditioners as well as installing shade covers on windows. It seems to be working. Minkus said that when the air conditioner broke at her store this spring, she and her coworkers received heating allowance for three consecutive days. A technician came the following week to fix the equipment.

Homegrown management did not respond to Grist's request for comment.

Homegrown isn't the only food chain where heat and faulty cooling systems have caused labor issues: Last summer, workers at a Starbucks in Houston, Texas, went on strike because of sweltering heat in stores.

“Last summer, our air conditioning didn't work, forcing us to work in temperatures between 80 and 85 degrees Fahrenheit,” Starbucks barista Madeline Austin, an activist with Starbucks Workers United, said in a statement. “Managers knew for months that the air conditioning wasn't working properly, but they refused to listen to our pleas to get it fixed.”

Starbucks' union is currently negotiating with the coffee chain over a “basic framework” to help forge a contract at the store level, and Austin said workers are fighting for “universal safety standards” to mitigate extreme heat.

In response to a request for comment, Starbucks said it is committed to keeping employees and customers safe and regularly reviews stores. “When an issue in a store poses a threat to the safety of our partners, we respond with great care and urgency,” the company said in a statement. (Starbucks refers to all employees as “partners.”)

Starbucks' example demonstrates that sometimes the quickest way for restaurant workers to ensure their own safety during a climate emergency is to close: Starbucks Workers United confirmed that the air conditioning at a Houston store was repaired after employees went on strike.

Homegrown workers understand this well: In addition to heat allowance policies, they've included a clause in their contracts that allows them to leave work because the store is too hot without facing disciplinary action. Minkus and Smith say workers are already taking advantage of this policy, with staff ready to just call it a day if it gets too hot.

Minkus described working in 88C heat next to 600C ovens as “miserable”. “So a lot of workers are leaving early. One factory closed early because it was too hot for everyone.”

Smith said when Homegrown employees first came to the negotiating table, they were fighting for better air conditioning. “That's still what we're asking for,” he added. “The heating allowance is nice, but we really want our workplaces to be at a moderate, safe temperature year-round.” Until then, Homegrown employees know they'll get extra pay for working in the heat. Smith said his stores have received 10 or 15 days of heating allowance since the contract went into effect in March.

Seth notes that extreme heat is increasingly affecting workers across industries, especially those who work outdoors, and that heat has come up as a topic in other foodservice contract negotiations. For Karmika, the connection between climate change and unions takes on even more urgency when considering productivity demands on workers. “In the service industry and many others, employers continue to try to force workers to produce more for less,” she says, adding that “as a result, workers often find themselves in situations where they are forced to work more and faster while facing severe staffing shortages,” which can exacerbate the effects of heatstroke.

As the labour movement continues to be affected by the climate crisis, activists like Kalmyka want to help workers connect their struggles with global ones. To her, the connection between worker exploitation and man-made climate change is clear: “They both have the same root cause, which is putting profits above people and the planet.”