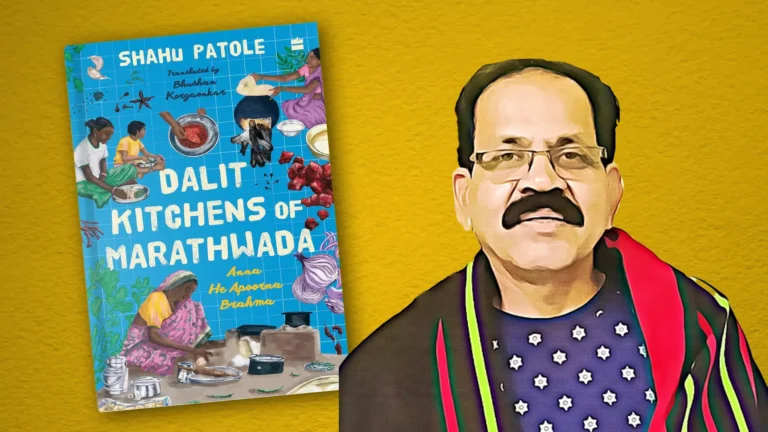

Shahu Patole, a resident of Aurangabad, is an unlikely champion of Dalit identity. He never planned to become a political activist fighting for the rights of a community that has been oppressed by upper castes for centuries. But he published a book in Marathi that Anna He Apurna Brahma He unintentionally began his journey as an activist after publishing his book, Food Is an Imperfect Truth, in 2016. It was recently translated into English by Bhushan Korgaonkar. The Dalit Kitchen of Marathwada: Anna He Apoorna Brahma (HarperCollins), Patole takes on the role of a pioneer who not only allows new readers to discover the hidden wonders of Dalit cuisine but also sheds new light on the oppression Dalits have faced for centuries.

The book breaks new ground in the ever-expanding world of Dalit literature and unintentionally brings him to the forefront of the narrative. Anna He Apurna Brahma A departure from traditional Dalit literature that has primarily focused on social conflicts, unrest and their impact, this is one of the first books to focus on the food of the oppressed castes and provides a detailed analysis of why the food eaten by the upper castes is different from that of the opposite caste in society.An anthropological study in the guise of a cookbook, this book features recipes that provide a comprehensive analysis of how socio-religious rules impart a caste hierarchy to food as well, resulting in the food of different strata of society occupying the same political and geographical region being quite different.

Dalit food: Hidden in plain sight

It all began in the early 1990s, when Patole noticed an increase in articles about food in newspapers. He realised that none of those articles mentioned the food of his community. “Even Marathi newspapers had started to feature more on food, but none of them mentioned the food of my community. So I sent a few articles about the food of my community, the Mann people of Marattawada, to newspapers. They sent my articles back. Those were the days when rejected articles used to be sent back to the writers,” Patole recalls over phone from Aurangabad. He now splits his time between Kangaon village in Osmanabad district and the city since retiring from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting in May 2021. His last posting was at Durdarshan in Mumbai.

In the first decade of the new century, he sensed a renewed surge in coverage of food and cuisine in newspapers. “Friends encouraged me to write, but I decided not to ask newspapers, as the material I had was enough for a book,” Patole says. “The book focuses on the food culture of the Mang and former Mahar castes, which are fundamentally different from the other two (upper) Dalit castes. The aim of the book is to document only the food culture of these two (lower) castes,” he writes.

Vegetarianism and non-vegetarianism

As anyone familiar with caste dynamics in India knows, the biggest difference between the food of the upper and lower castes lies in meat consumption. While many of the upper castes are vegetarian, meat consumption, including beef, is common among lower caste Hindus in almost all parts of India. A distorted version of this reality has given rise to myths about Indian vegetarianism, the consequences of which do not bode well for the health of the country. This was seen in the recent campaign for Lok Sabha Elections 2024.

Nearly a third of Patole's book is devoted to a detailed examination of the questions that need to be answered to understand why a community eats the food they do. Patole lucidly explains the origins of vegetarianism and non-vegetarianism in certain communities. His detailed descriptions of the various caste divisions and the hierarchy within the Dalit caste are eye-opening. “In Hinduism, class system, caste system and food culture are 'three sides' of the same coin,” he writes succinctly.

In a key section, Patole tries to answer the question, “Why did beef and pork become part of the diet of only these communities?” He writes: “In Hinduism, the earlier permissible practice of eating cow and bull meat gradually changed over time into a highly anti-religious and socially unacceptable practice. Yet, it continued to be a significant part of the diet of the Mahar and Mang castes for centuries… Why should these two castes suffer such a fate? They were the village sweepers. Were they subjected to this cultural and religious trapping so that they could continue their work without raising their voice?”

It is not difficult to understand the reason behind the anxious tone of the first half of the book. The author raises pertinent sociological questions and seeks to answer them from the perspective of a community that has been discriminated against since time immemorial. The anger is also at the hands of unintentional cultural misinformation. The author writes: “The food culture of a higher caste or class has been categorised and accepted as the food culture of an entire society, region or nation…This means that the superiority accorded to a class extends to its food and language as well.”

His tone becomes more light-hearted as the book moves from sociological commentary to chronicles of festivals and other events, followed by details of rituals with recipes for dishes for special occasions, a comprehensive list of recipes for different types of meat, and a chapter dedicated to vegetarian cooking.If there's one reason that food connoisseurs should pick up this book, it's for its encyclopedic list of recipes that are little known outside the community.

What's interesting about Patole's recipes is that they never give measurements. “Several people have pointed that out to me, but in traditional kitchens, our mothers never cooked by measuring with spoons or cups. No matter how big a family they had to feed, they knew exactly how much they needed without measuring,” Patole explains. It's no surprise then that he also dedicated the book to his mother, Gunabai Manik, quoting her: “Cooking is a game of estimation, sleight of hand and hypnotism.”

Dalit identity

Even Patole himself struggles to explain why there was no comprehensive work on Dalit cuisine till the publication of his book, given that Dalit literature emerged as a distinct field way back in the 1970s. It was a direct result of the emergence of the Dalit Panther movement, started in June 1972 by educated youth from the then slums of Bombay and inspired by Bhimrao Ambedkar and the Black Panther Party in the US. Patole adds: “Prior to the emergence of Dalit literature, Marathi literature was divided into two streams: Marathi Saraswat literature, which was mainly urban, and Gramin (rural) literature. The latter often contained references to Dalits, who were outcasts in the villages but were an integral part of it. There were occasional references to Dalit cuisine, but those references were sporadic.” He says that the names and references to food mentioned in his book were culled from leading Dalit autobiographies, such as Daya Pawar's. Balta, Shankarrao Kalat Talal AntarlPrivate Detective Song Kambul Atavaningche PaksiUttam Bandhu Tupe Kacavalchi Potaand Sharankumar Limbare. Great.

But having a Dalit identity is still a work in progress. As Patole writes, one reason is that “Dalits, who occupy a significant and well-established place in all sectors of society in Maharashtra today, feel uncomfortable when the topic of food habits and culture comes up.” The other is a generational shift that followed the mass migration of Mahars and Mangs from Marathwada to Bombay and Pune in search of livelihood after the 1972 drought in the region. Patole says, “In Mumbai, there is a change in attitude because they don't care about caste, they only care about work. The younger generation who grew up in Mumbai and elsewhere don't even know the situation their parents faced.” In both scenarios, food habits are affected by the adoption of urban culture. “Rice, wheat, vada pav, etc. are now part of our diet that were not part of the traditional diet,” Patole says, citing examples. That's why it becomes even more important to document this.

Patole, who spent three years at Kohima radio station as AIR news head, says there is great acceptance among the Nagas due to their common food culture. “It was a surprise for them that Hindus also eat a variety of meats,” he says. A caste-free India is not yet a reality, but it may be time for more books on different Dalit castes and more restaurants serving food from these castes.