The longtime BU faculty member, TV host, and friend of Julia’s has a new cookbook—and a new generation of fans on social media

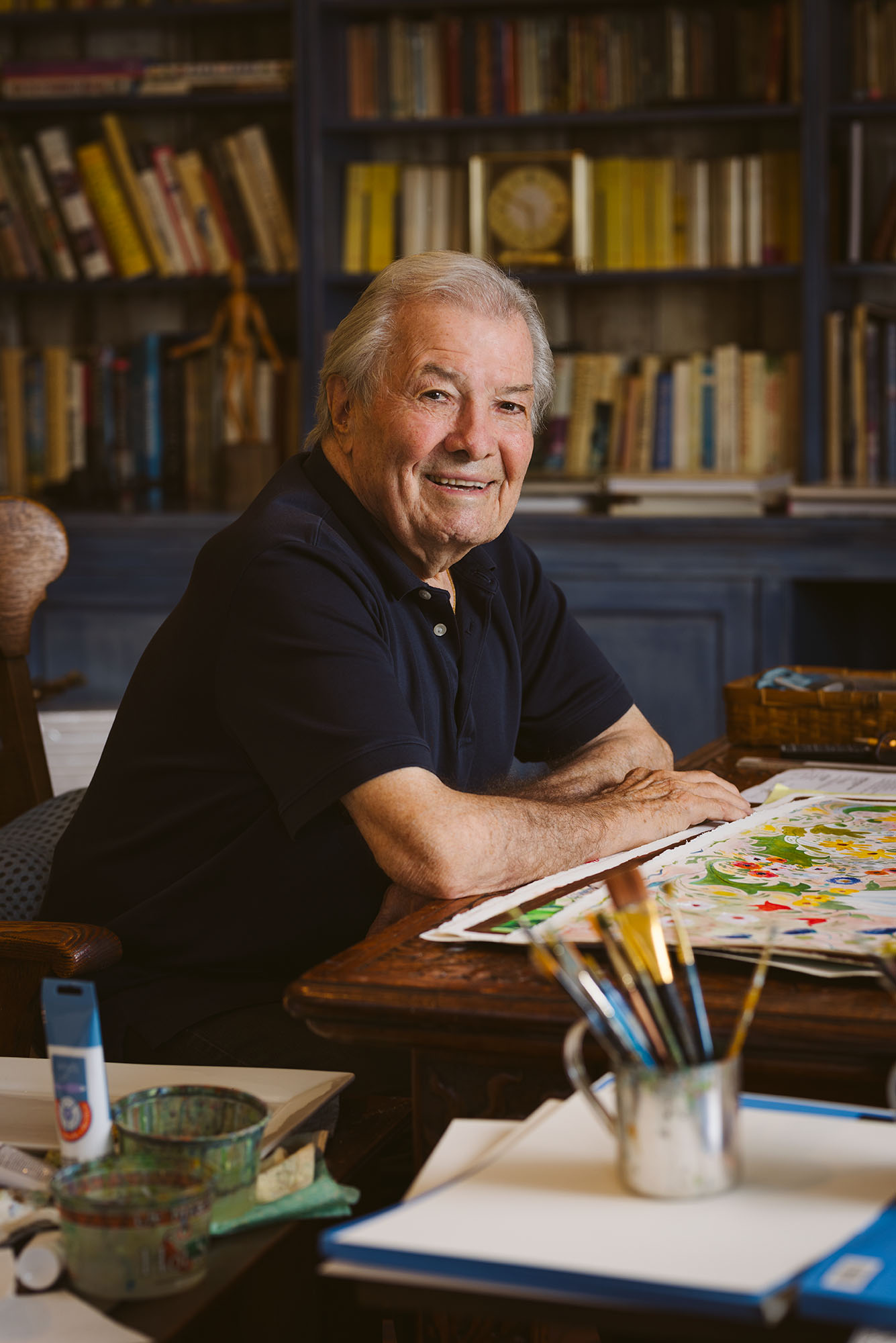

I arrive at Jacques Pépin’s Connecticut home on a hot August day and knock on the front door. I hear footsteps approach, followed by a high-pitched bark. The door opens, and I’m face-to-face with the legendary chef I grew up watching on TV as he whipped up cassoulet and baked apple tarts. Dressed in a dark blue polo shirt, gray pants, and white slip-on shoes, Pépin is a spry 88. “Welcome to my home,” he says in a quiet voice, his French accent still pronounced after all these years living in the US. He smiles warmly, shakes my hand, and introduces me to the source of the barking: Gaston, his nine-year-old black toy poodle.

We pass through the brick-walled foyer, Gaston at our feet, and Pépin (Hon.’11) tells me the home used to be a brick factory. The walls are dotted with photos from his storied life, including images of Pépin with legendary chef Julia Child (Hon.’76), his friend of 44 years and frequent collaborator, who died in 2004. The two costarred in PBS specials and their own show on the network, and teamed up to establish a certificate program in the culinary arts and a master’s degree program in gastronomy at BU.

His collaboration with Child is just one highlight of his long and luminous career. Pépin has cooked for heads of state, written more than 30 cookbooks, and received 16 prestigious James Beard Awards. But teaching has been the hallmark of Pépin’s work, ever since he published his groundbreaking first cookbook, La Technique, almost 50 years ago, and appeared on his first TV series, in 1982. He continues to teach in BU’s culinary arts certificate program each semester, and he’s devoted himself to opening doors to culinary training for the disenfranchised through his Jacques Pépin Foundation, established in 2016 with his daughter, Claudine (CGS’88, CAS’90), and son-in-law, Rollie Wesen.

Pépin, who recently completed a book tour for his newest cookbook, Jacques Pépin Cooking My Way: Recipes and Techniques for Economical Cooking (Harvest, 2023), seems equally adept at conquering every medium. He’s become a social media star, showing a new generation of cooks on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and YouTube how to make a perfect egg, butterfly shrimp, or prepare a simple green salad. “I don’t really go on things like Facebook or Instagram much,” he says. “Claudine was the one who asked me, ‘Why don’t you make some short videos?’ Now, we’ve done more than 300.”

Making Something Simple

At Pépin’s home, we make our way into the kitchen—his kitchen, not the second one he had built at the back of the property many years ago for interviews and cooking demos. His wife, Gloria, who died in 2020, requested the space to prevent the constant flow of media from circulating through their home. The room has none of the oddly minimalist aesthetic—all gleaming stainless steel appliances and empty, pristine counters—we associate with the archetypal chef’s kitchen.

It feels cozy, lived-in, in the best way. An enviable collection of pots and pans hangs on one wall. Four utensil holders brim with kitchen tools, and an orange-enameled crock sits on the back stove. The island has a built-in block for every sort of knife, a second cooktop, and an array of oils and vinegars.

Pépin’s personal touches are everywhere in his kitchen. A longtime painter and avid craftsman, he points to the tiles he painted, featuring his favorite foods and ingredients—a baguette, a chicken, a lobster, a mushroom, carrots. Above the range, there’s a mosaic he designed depicting a kitchen with an open window looking out on the water.

But mostly, this kitchen is where his culinary artistry takes place, which he graciously showcases by preparing flapjacks with onions and chives from Cooking My Way. The cookbook is filled with recipes that call for seasonal ingredients and leftovers and espouses ways to avoid wasting food. The flapjacks are savory pancakes that come together with stale bread.

“It’s part of the DNA of most people in the world to not waste food,” Pépin says. “In France, I think it’s part of tradition, but maybe even more so for me because I was raised during the Second World War. My mother was a very great cook and had a restaurant, but she was very miserly and used absolutely everything in the kitchen. That’s what I was raised on. There is probably no country in the world that wastes as much food as we do in America.”

Pépin wields his knife with the speed and precision of an accomplished chef. He moves assuredly through the kitchen, explaining as he goes and revealing the culinary alchemy that occurs when you combine stale bread with some milk, an egg, onion, chives, and seasonings. He dollops yogurt onto each pancake and tops them with chive blossoms.

“Of course, the presentation of a dish is important,” he says. “But it’s often become too complicated and unnatural in the last few years, using what I call ‘punctuation cooking,’ where they do a drop [of sauce], a drop, a comma, a drop, all around the plate.”

His flapjacks are unfussy—and delicious. (Mark Bittman, journalist, author, and former New York Times food columnist, wrote on his website in October, “Jacques is obviously a famous chef, and a brilliant one, but he’s also the best home cook I’ve ever met. He’s a chef with a home cook’s sensibility, and has never stopped being inventive.”)

“There is nothing wrong with making something simple,” Pépin says. “I remember times going to BU and teaching classes where a student wanted to do something very complicated. And I’d say, playing devil’s advocate a bit, ‘How about you try a hot dog?’ The point is, whether it’s a hot dog or a ham sandwich, there is always one which is better. It doesn’t have to be that complicated if it’s done well.” (In one of his Instagram videos, Pépin actually prepares a hot dog—“the curly dog”—with homemade relish. “You do that for the kids,” he says, “they will love you.”)

Pépin’s 1976 cookbook La Technique was one of the first to show, step-by-step through close-up photos of his hands, essential cooking methods, including how to mince an onion or carve a turkey. The techniques are still relevant today, he says.

“I don’t cook the same way that I did 50 years ago,” he says, “but the way you sharpen a knife, poach an egg, or slice an onion—that never really changes.”

A Social Media Hit

Pépin has made cooking a family affair, bringing his daughter, son-in-law, and granddaughter on episodes of his shows and collaborating with them on cookbooks. Claudine, who studied philosophy and political science at BU and appeared with her father in their 1996 show, Jacques Pépin’s Kitchen: Cooking with Claudine, manages his social media. She encouraged him to start posting short cooking videos during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The videos were an immediate hit, especially on Facebook, where his followers grew from around 300,000 to almost 2 million.

“The response after the first one, which was just a really rough cut, taken on a phone, of him making a vinaigrette in a jar, was insane,” says Claudine. (That video now has more than a million views on Facebook.) “And he really likes making them. At the time we started doing them, my mom was still alive. She just looked at me and said, ‘Oh, thank God, because I don’t know what to do with your father.’”

Pépin’s granddaughter, Shorey Wesen (COM’26), who’s studying public relations and psychology at BU, says she didn’t grasp the magnitude of her grandfather’s celebrity until they were on a book tour together for their cookbook, A Grandfather’s Lessons: In the Kitchen with Shorey (Harvest, 2017). “There was one specific book signing that we went to where people were lined up around the block to get his signature,” she says. “I thought, ‘Wait a minute—people really care about this.’”

Pépin’s joyful, approachable way of explaining cooking techniques—from the basic to the more complicated—is at the root of his enduring popularity. “My dad is the biggest jokester,” says Claudine. “He loves a good joke. He’s the guy who is so excited to tell you the joke that he’s laughing before he finishes it because he thinks it’s so funny. And chances are, it is so funny. But my father is first and foremost a teacher, and he values education and teaching technique a tremendous amount. You can have the most beautiful ingredients in the entire world, but if you don’t know how to chop an onion, what are you doing?”

Lessons From Hojo’s

Pépin developed his passion for cooking while working in his mother’s restaurants. Born in Bourg-en-Bresse, France, near Lyon, he came of age during World War II and has never forgotten the food shortages of the time. He quit school at 13 to take on a culinary apprenticeship and, a few years later, moved to Paris to work in the kitchens at the renowned Hotel Plaza Athénée.

In his early 20s, he was called to serve in the military, assigned as the personal chef to three French heads of state, including President Charles de Gaulle. That may sound glamorous, a stepping stone to celebrity, but Pépin says chefs weren’t afforded the same level of respect they are today.

“It was a different world,” he says. “You have to think of things in the context of the time. Chefs weren’t looked at the same way as now. A cook’s place was in the kitchen, that was it. I served people like Eisenhower, Tito, Macmillan, Nehru—many heads of state from around the world—but no one would ever mention the chef. At that time, the cook was at the bottom, socially.”

In the video above, Pépin works with students in BU’s test kitchen in November 2023. He and Child teamed up to establish a certificate program in culinary arts and a master’s degree program in gastronomy at BU in the 1980s and 1990s. Photo by Cydney Scott. Video by Devin Hahn

In 1959, Pépin moved to New York City and became a chef at the now-closed French restaurant Le Pavillon, and attended an English for international students program at Columbia. At Le Pavillon he became acquainted with Helen McCully, then the food editor of House Beautiful magazine, who introduced him to both Julia Child and James Beard around 1960.

Soon, through other connections he made at Le Pavillon, he had two enticing job offers. One was an invitation to become President John F. Kennedy’s White House chef. The other was to helm research and development for the Howard Johnson’s restaurant chain, an offer that came from Howard Johnson himself, a regular at Le Pavillon. At the time, Howard Johnson’s had more than 1,000 locations and was the biggest restaurant chain in the country. “It was bigger than McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Burger King—all three together,” Pépin says.

He chose Howard Johnson’s. “Again, in the context of the time—I didn’t go to the White House because I didn’t realize the kind of potential that held,” he says. “I have a picture hanging on my wall of [my late friend] René Verdon, who did become the White House chef. He sent me this picture of him with the president a year or two later.”

Pépin studied American dining habits and was responsible for developing and improving dishes. He introduced fresh onions and butter, rather than dehydrated onions and margarine, for instance, and developed dishes like clam chowder and chicken pot pie.

The decade he spent with HoJo’s prepared him to open his own restaurant, La Potagerie, on 5th Avenue in New York City, which he operated for five years.

After a bad car accident left him with devastating injuries, including two broken arms, he couldn’t sustain the hours spent on his feet in a kitchen. He began working as a consultant for the famed Russian Tea Room and the World Trade Center’s commissary. “They served 40,000 people a day at the World Trade Center,” he says. “I never would have been able to do that without the training at Howard Johnson’s.”

After his accident, Pépin moved to Madison, Conn., in 1974 and turned his attention to writing cookbooks and columns for publications like the New York Times. He taught in culinary programs in New York and cooking classes at BU’s School of Hospitality Administration.

Jacques and Julia

Pépin remembers his first meeting with Child, in 1960: “Helen [McCully] said to me, ‘Oh, that woman who is writing the book Mastering the Art of French Cooking is coming to New York, so we’re going to cook for her.’ So, we did, and then I became friends with Julia. We spoke French the first time we met because her French was better than her English, having just come back from living in France, and I had only been in [New York] for a few months.”

While the two had good-natured disagreements on certain approaches to cooking, both believed that food hadn’t been taken seriously as a course of academic study. They set out to change that.

Pépin had already been teaching at BU for many years and, in 1989, he and Child helped establish a semester-long certificate program in the culinary arts at BU’s Metropolitan College. But they also envisioned a program with courses both in the kitchen and the classroom, in which students could study food through lenses of history, sociology, anthropology, literature, and the arts.

“Julia had said to me, ‘We should start a program in gastronomy. That doesn’t really exist in colleges,’” says Pépin. They wrote to BU President John Silber (Hon.’95), who gave the okay to launch a master’s degree in 1991. Pépin and Child taught the program’s first course. “It is still one of the only programs of its kind in the country,” Pépin says. “It’s been very gratifying.”

Whether it’s a hot dog or a ham sandwich, there is always one which is better. It doesn’t have to be that complicated if it’s done well.

“Jacques’ impact on the program is clear—we engage our hands and intellects together in the kitchen,” says Megan Elias, a MET associate professor of the practice and director of the Gastronomy Program. “His visits every semester are really magical times, because he brings joy with him when he enters our kitchens. He’s approachable and supportive. He is interested in the students, and it’s clear that he loves to cook with people, not just for them.”

Pépin radiates that joy in his television programs and social media videos. He landed his first TV show, Everyday Cooking, in 1982. In the years since, he’s starred in many PBS cooking programs, including one with Child, 1999’s Julia and Jacques: Cooking at Home. He says the idea for the show was sparked by the cooking demonstrations they’d given at BU. (Their relationship was the same both on camera and off, he says, with a fun, easy rapport and deep respect for each other’s approach to cooking—even if they occasionally disagreed on whether a dish needed more salt.)

Pépin’s love for teaching inspired the mission of his charitable foundation. In 2016, he, Claudine, and Rollie Wesen created the Jacques Pépin Foundation, with the goal of expanding culinary training opportunities for those who are disenfranchised or underrepresented in the field. Wesen, director of the foundation, wanted to ensure that Pépin’s legacy as a culinary educator is never forgotten. “Jacques said that learning to cook is something that can really help people who need a hand up in society,” says Wesen. “That started us on this path of supporting community kitchens that are all around the country.”

The foundation has provided over $1 million in grants to support more than 100 community kitchens and culinary training programs in Cleveland, Ohio, Tacoma, Wash., and elsewhere.

“We wanted to help people who have been a bit disenfranchised in their life—perhaps people who have come out of jail, people without housing, recovering addicts, veterans looking to enter a new career,” says Pépin. “The grants we give to the different organizations are not necessarily always to buy new stoves. Recently, we helped one organization buy a washing machine for the students to wash their uniforms. This has been quite rewarding because I feel that if somebody is interested in cooking and likes working in the kitchen, we can probably, in six weeks, teach you how to peel an onion and poach an egg, very simple stuff like that, and get you started in the kitchen. And if you stay there for five years, maybe you’re the chef. People can perhaps go on to open a restaurant. You can redo your life this way.”

The Art of Cooking

Back at Pépin’s home on that August day, he gives me a tour of his second-floor art studio, a space filled with natural light. For nearly 50 years, he’s hand-painted menus for meals he has cooked for guests. He’s kept them all. In 2018, he published Menus: A Book for Your Meals and Memories (Harvest), a journal of sorts whose pages are bordered with designs he painted, so people can fill in their own menus. In 2022, he published the New York Times best-selling book Art of the Chicken: A Master Chef’s Paintings, Stories, and Recipes of the Humble Bird (Harvest), which features scores of his colorful, whimsical works.

Pépin sees similarities between how he approaches two of his passions: cooking and painting. “Sometimes I start a painting, and I don’t really know exactly where I’m going. But at some point, you start responding to it. You put a shape there, or a color there, because it feels good without even trying to validate it in any ways,” he says.

Cooking involves similar intuition: “Let’s say you are making a chicken sauté with morels,” he says. “The same night, you may do that order six or seven times. And if someone were behind you mocking exactly what you’re doing, they’ll see that for those seven times, you did it differently. But they all came out exactly the same. You make different adjustments without even thinking about it—you taste, you adjust, you taste, you adjust.”

From Jacques Pépin Cooking My Way: Recipes and Techniques for Economical Cooking by Jacques Pépin (Harvest, 2023)

I always use leftover bread in one way or another. Here, I make a flapjack by soaking whatever type of leftover bread I happen to have with milk, then adding egg, onion, and chives. You could add garlic if you want and other herbs; I’ve also made a sweet flapjack with stale bread, milk, egg, and then sugar, and leftover fruit, like apple or banana. Use whatever you have on hand.

Yield: 3 pancakes

Ingredients

- Leftover bread cut into 1/2-inch pieces (about 1 cup) 1/4 cup milk

- 1 large egg, preferably organic

- 3 tablespoons coarsely chopped onion

- 2 tablespoons coarsely chopped fresh chives

- Pinch dried oregano

- Pinch each fine sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

- 2 tablespoons peanut oil

- Sour cream, for serving (optional)

Directions

Combine the bread, milk, egg, onion, chives, oregano, salt, and pepper in a small bowl. Mash with a fork until well combined.

Heat the oil in a large skillet and add three scoops of the mixture to make three flapjacks. Flatten the mixture with a fork to about 1/2 inch thick and cook until brown, 2 to 3 minutes on each side. Serve with sour cream, if desired.