Okina Kitchen, an organic baking mix company originally based in Kailua, has sparked a debate within the Native Hawaiian community about cultural appropriation and intellectual property.

“Okina,” or glottal stop, is one of the 12 letters of the Hawaiian alphabet and is currently trademarked by the company's owners.

Okina Kitchen's ownership of the trademark on the word “Okina” has raised many questions, especially to Vicki Holt Takamine, kumu hula of Halau Pua Alii Ilima.

“What is your respect for the Native Hawaiian community? Why do you feel entitled to appropriate Native Hawaiian language to promote your business? Are you using Native materials? Are you giving back to the community?” Holt-Takamine asked.

“When you do something, there needs to be a reason why you're doing it, and I don't see that here. I don't see the connection to the Hawaiian community. I don't see the benefit to the Hawaiian community,” she said.

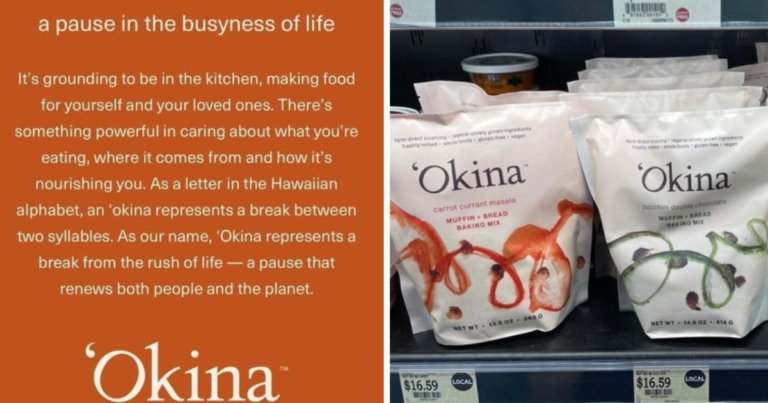

Marketing materials for Okina Kitchen circulating on social media state: “Okina, a letter in the Hawaiian alphabet, represents the break between two syllables. Our name, Okina, represents a break from hectic lives.” Okina Kitchen founder Kristen Eldredge did not respond to HPR's repeated requests for comment.

'Olelo Hawaii and Business

Okina Kitchen is not the first company to incorporate 'olelo Hawaii into its name, but Noah Haalilio Solomon, a Hawaiian language professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, said he welcomes the use of 'olelo Hawaii in businesses and said he believes most people in the Hawaiian language revitalization movement do too.

“We are swimming on a Hawaiian beach.” Makemake is our emotional support and shows that Hawaiian culture is rooted in our lives. I lived in Hawaii and on this island about 1940s and 50 years ago. On this island there was a small island called Puke Wehewehe. “Nui na Kumu Ike.”

Solomon said that while “'olelo Hawaii” is used in businesses, he doesn't just pick the first word he sees in a Hawaiian dictionary. Hawaiian resources are varied. And incorporating “olelo Hawaii” into a business comes with kuleana, he said.

“One day you will be able to go to the beach in Hawaii. “He gazes upon the beautiful scenery of the Hawaiian Islands and all its beauty, and in the midst of it all the moon and the flower nymphs and the hikimaiana.”

Solomon said using a Native Hawaiian name for a business comes with a responsibility to support “Ōlelo Hawai'i” so the language can thrive for generations to come.

'Ōlelo Hawaii and U.S. Intellectual Property Law

So what exactly does U.S. intellectual property law say about “Ōlelo Hawaii”?

Makarika Naholowa'a, executive director of the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, said there are currently no special legal protections for the Native Hawaiian language.

“Just like English and every other language, it is open to privatization and quasi-monopoly through the intellectual property system,” Naholova said.

Naholowa'a said the government could monitor the issue closely and actively advocate for Hawaiian to be treated equally with English.

“For example, there is an exception in the intellectual property system that says you can't monopolise a non-distinctive name as a business name,” Naholova says. “So if it's a generic name for a product, there's a rule that says you can't monopolise that name. Can you use that name? Yes, you can, but you can't monopolise it as a trademark.”

“However, there are parts of U.S. intellectual property law that are inherently at odds with Native Hawaiian worldviews and beliefs about how languages should be managed. Naholowa'a said one of the reasons for the outcry over the use of Native Hawaiian names is that Native communities have had to fight incredibly hard to keep their languages from becoming extinct.”

“When we see non-Indigenous brands using the name as a marketing ploy, it not only goes against our sense of justice and fairness, but it probably creates confusion,” Naholova said. “Fundamentally, this area of law around trade names and trademarks is to prevent confusion. You see an Indigenous trade name and you think there's an Indigenous provenance behind that name, and if there isn't, it's deceptive.”

Naholowa'a said bluntly that despite this system of intellectual property laws being in place, there is no organisation funded to take legal action when someone breaches the rules.

“Until someone cares enough about protecting this language in this way and the funding is there, there's no point in someone breaking the rules because there's no one in a position to take the legal action necessary to stop it,” Naholowa'a said.

Paoakalani Declaration

This is not the first company to copyright or trademark Hawaiian language, music or culture.

In 2018, a Chicago-based company sent a cease and desist letter to a company of the same name, attempting to enforce its rights to the trademark “Aloha Poke.” In 2002, Disney acquired the copyright to a Hawaiian song composed by King Kalakaua and Queen Liliuokalani.

“You can't trademark 'Ōlelo Hawai'i. You can't own it. It belongs to all of us who are lāhui,” Holt-Takamine said. “If you trademark it according to the Western system, it prevents other people, including Native Hawaiians, from using it for their own purposes.”

Holt Takamine has been working for decades to raise awareness about the challenges Native Hawaiians face when companies try to trademark their culture, language and music.

In 2003, she and other kumu hula, cultural practitioners, lawyers, and University of Hawaii Law School students came together to draft a document asserting Native Hawaiian intellectual property rights. The Paoakalani Declaration was recognized a year later by a resolution of the Hawaii State Legislature, but no steps were taken to codify any of its parts.

“The government should adopt the Paoakalani Declaration as policy,” said Holt-Takamine. “My concern is that the government should not own our intellectual property because they can sell it or use it or give licenses to other people to use it. We, as lāhui, must maintain our sovereignty by asserting our intellectual property rights.”

Native Hawaiian Intellectual Property Rights Working Group

Holt-Takamine is one of nine members of the new Native Hawaiian Intellectual Property Working Group established by House Joint Resolution 108 of 2023. The group is led by State Assemblyman Darius Kila, who represents House District 44 (Maili, Nanakuli, Honokai Hale, Ko Olina).

“Every state legally protects its identity in marketing, right? You look at the state of California and the grizzly bear logo. Potatoes in Idaho, peaches in Georgia, anything that's synonymous with the state or culture is protected because it has a fiduciary benefit and benefit,” Kira said.

But there are fewer protections for Hawaii and its culture and language, he said.

“In its most diluted, basic form, Native Hawaiians don't think of this practice and culture that we have inherited as our own, but now we live in a Western culture and society where people are exploited and things are taken from us without our permission,” Kira said.

“There are no safeguards in place, so there's very little that anyone can regulate what is authentic and what is not. And to some extent, Native Hawaiians don't see the benefit of everyone else appropriating their culture who is not Native Hawaiian.”

The working group is scheduled to meet for the first time on June 24. Other members of the group are:

- Kumu Hula Vicki Holt Takamine, Halau Pua Alii Ilima (Oahu)

- Kumu Hula Cody Pueo Pata, Halau Hula O Ka Malama Mahilani (Maui)

- Elena Faden, Council on Native Hawaiian Education (Oahu)

- Hailiopua Baker, Director of Hawaiian Theatre Programs, University of Hawaii at Manoa (Oahu)

- Keopulani Leiritz, Hawaii Office (Oahu)

- Makarika Naholowa'a, Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation (Oahu)

- Nathaniel Naka, Civil Beat (Big Island)

- Uilani Tanigawa Lam, University of Hawaii William S. Richardson School of Law (Oahu)

- Zachary Alaka'i Lam, Native Hawaiian musician (Oahu)

Kira hopes the group will serve as a precedent and model for other Indigenous communities grappling with the same issues.