Dining room (Photo by James Caulfield)

On a crisp fall day in early December 2023, a truck pulled up in front of the landmark Glessner House at 1800 S. Prairie Avenue. Soon came a massive oak sideboard weighing over 400 pounds and all the parts needed to assemble a 16-foot extended dining table. The same scene would have unfolded in late November 1887, in anticipation of the Glessner family moving into their new home the following week. Every detail, from the intricately carved panels to the iron brackets and screws that no one could see, had been meticulously replicated, giving the Glessners the chance to duplicate their original furniture. You couldn't tell the difference in the furniture. I'm talking about new furniture.

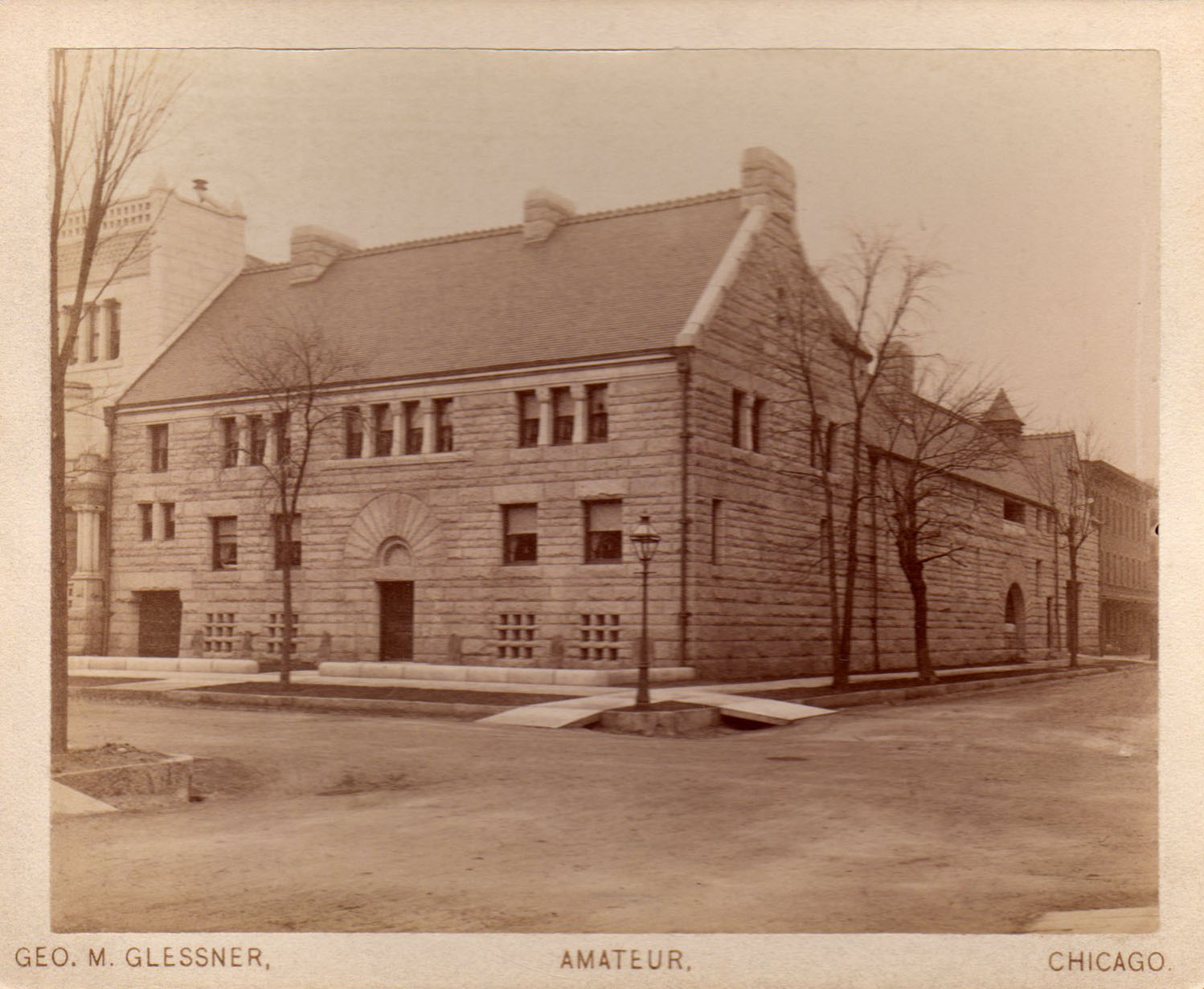

The story begins in the spring of 1885. John and Frances Glessner selected America's most famous architect at the time, Henry Hobson, to design their new home on Chicago's exclusive Prairie Avenue, home to Marshall Field, George Pullman, and most others. It has expanded. A wealthy man from Chicago. Richardson's innovative design, which placed the main rooms in a south-facing courtyard, was not appreciated by most of the neighbors, who called it a fortress or a prison. “I don't know what I've done in my life that I have to see that every time I step out my front door every day,” said Pullman, whose home was located around the corner from Glessner's. It is reported that.

exterior

The house's exterior, clad in rustic Braggville granite, represented Richardson's mature style (which became known as Richardsonian Romanesque), and certainly gave it a fortress-like appearance; , the inside was warm and inviting. With his new 17,000-square-foot home, Richardson responded to Frances Glessner's desire to maintain the “coziness” of the small house (demolished in 1888) in which she lived at the time at Washington and Morgan Streets. I designed the room.

Richardson died in April 1886, shortly after finishing designing his new home. The building was completed under the direction of its successor firm, Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, which later provided Chicago with both an art museum and a public library (now the Cultural Center). Charles Coolidge, 28, one of the partners in the new firm and a close friend of the Glessners, designed the oak-paneled dining room furniture. This dining room is 18 feet by 27 feet, making it the largest room in the house. . The same quarter-sawn white oak used throughout the house for the moldings, fireplace, and staircase was chosen for the sideboard, dining table, and 18 chairs. The elegant sculpture captures the details of the historic Romanesque building on which Richardson based his design.

Dining room circa 1888

These pieces of furniture witnessed decades of the Glessner family's elaborate eight-course dinners, whose frequent guests included artists, architects, musicians, writers, and university presidents. As founders and major supporters of what is now the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, they welcomed major musicians of the time, including Ignacy Paderewski, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Enrico Caruso, to name a few. Theodore's first two music directors, Thomas and Frederick Stock, were regular guests and often celebrated Thanksgiving and Christmas with their families.

This furniture was manufactured by AH Davenport and Company, a prominent Boston-based interior decoration and furniture manufacturing company. The firm's chief designer, Francis Bacon, had previously worked as an architect at Richardson's firm, so it's no wonder Richardson often used the firm to execute his own designs. . Bacon is credited with contributing to the design of the Glessner family's Steinway grand his piano, which has a mahogany case with elaborate inlays combining various woods and mother-of-pearl. Davenport created numerous other pieces for the home, from the library's giant partner desk to the bedroom suite and various tables, chairs, and cabinets.

Davenport had an outstanding reputation. One of his largest orders consisted of his 225 pieces of furniture and ornaments for Iolani Palace, the royal residence of the rulers of the Kingdom of Hawaii, completed in 1882. Much of the original furniture remains in the house and is now open to the public. As a home museum. In the early 1900s, architect Stanford White commissioned Davenport to create furniture for the official dining room of his House of White during his Roosevelt presidency. Many of those parts are still in use today.

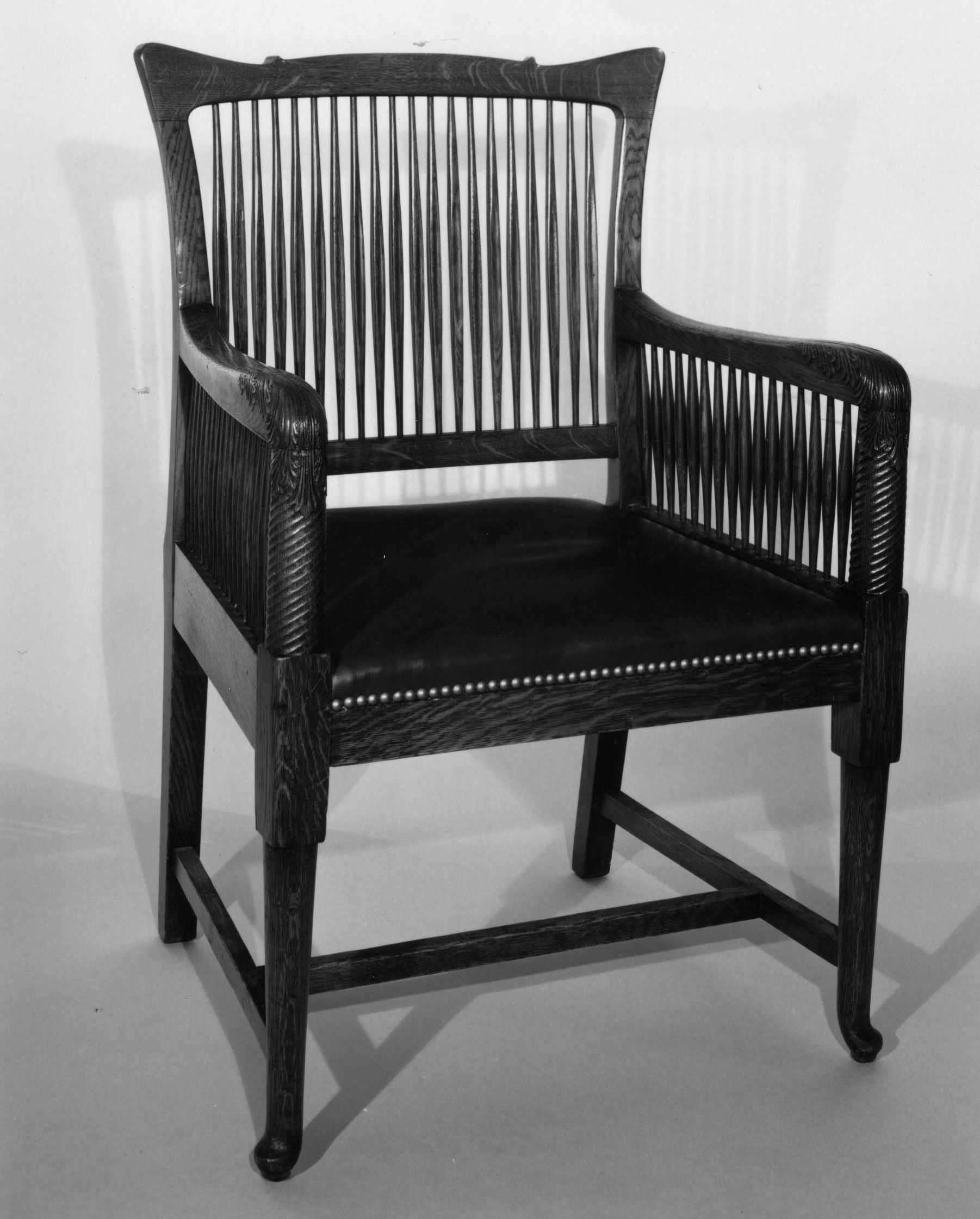

The Glessner family's dining table was six feet in diameter when closed. It was supported by four slightly tapered square legs, each decorated with an acanthus leaf and a front paw. He added 10 1-foot leaves and the table expanded to 16 feet, providing seating for 18 people. These chairs are similar in design to other pieces designed by Richardson, especially their interesting combination of Colonial Revival, such as the slender spindles reminiscent of the Windsor chairs, and Art Nouveau, such as the sinuous curves of the top rail. was. The two armchairs feature shallowly carved acanthus leaves on the armrests, gracefully curving directly into the spiral arm supports.

armchair

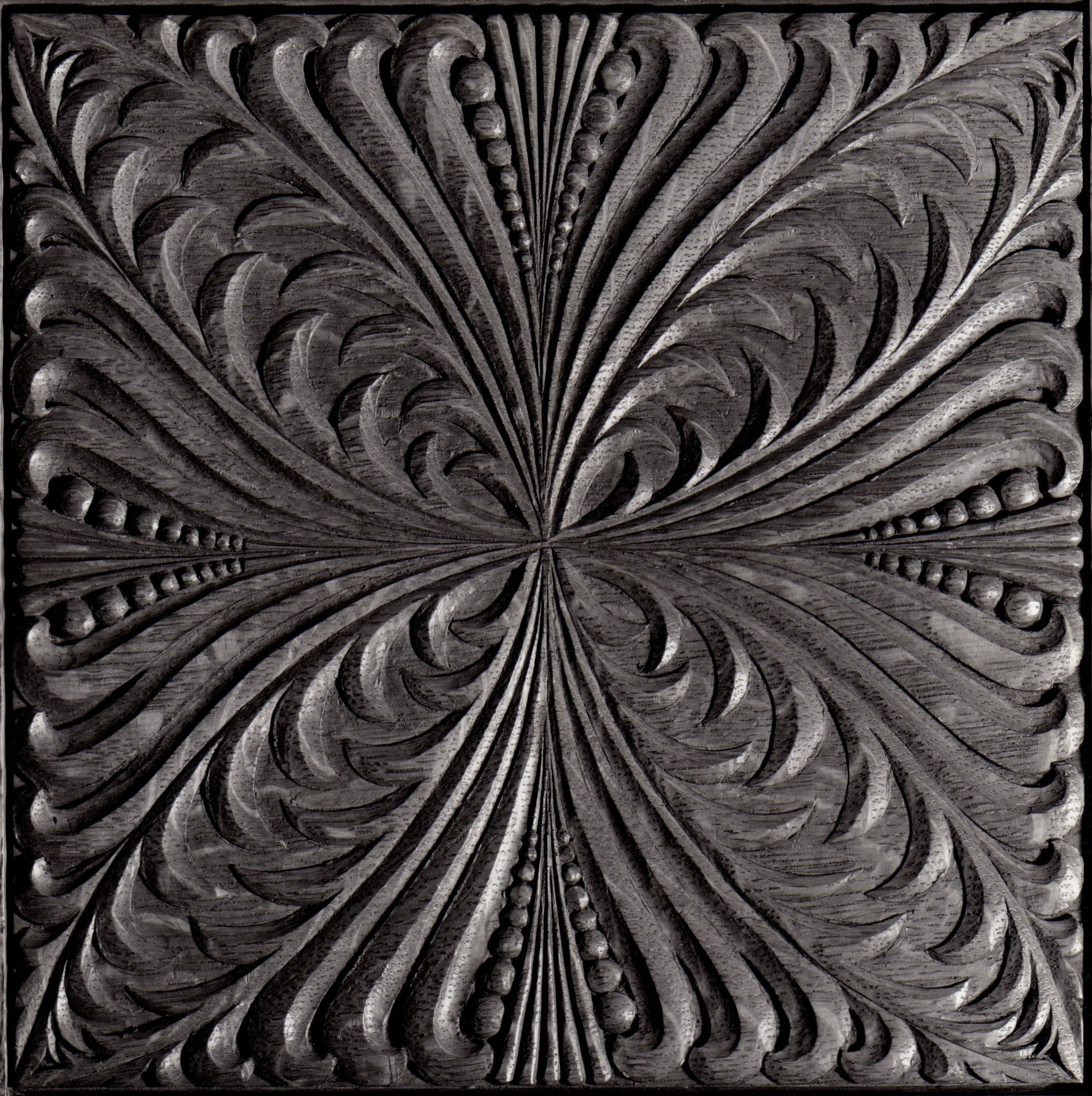

The sideboard had the best carved design. Although it is a free-standing piece of furniture, its proportions perfectly match the grid of oak panels behind it. The upper shelf, supported by his four elaborately carved columns, was designed to hold some of Glessner's favorite ornaments. There was ample upper space for placing serving trays, carafe, and other items used during meal service. His five carved panels, each with a unique design, decorate the back of the piece and the doors of his two cabinets.

The Glessners paid a total of $10,000 for all the Davenport furniture in their home. When John Glessner passed away in January 1936, the furniture in his dining room was appraised at just $101, but this was due to changing tastes and the country being in the midst of the Great Depression. is shown. Descendants removed most of the house's contents, but no one needed such huge dining room furniture, so it was donated to the Armor Institute (now the Illinois Institute of Technology) in 1938. when it was left in the building.

The furniture remained when Armor rented the house and eventually sold it to the Lithographic Technology Foundation, which moved the furniture to an upstairs hall and used the table for meetings and conferences. When the foundation moved to his Pittsburgh location in 1965, he sold the table, sideboard, and 14 side chairs for $250 because the house was scheduled for demolition. (The two armchairs and two other side chairs were left in the attic and were discovered when the house was saved from demolition and he purchased it in 1966).

For decades, a small table and sideboard sat in the dining room along with four surviving chairs, but they didn't begin to portray the elegance the room once had. In 2021, longtime mentor Alan Wagner and his wife Angie made a generous and visionary lead gift to recreate the table and sideboard. After extensive research, Patrick Burke of Atelier Burke in Newton, Wisconsin was asked to recreate the furniture. Burke had trained as a woodcarver in northern Italy and had all the skills necessary to recreate Coolidge's designs and Davenport's expert craftsmanship.

dining room 1923

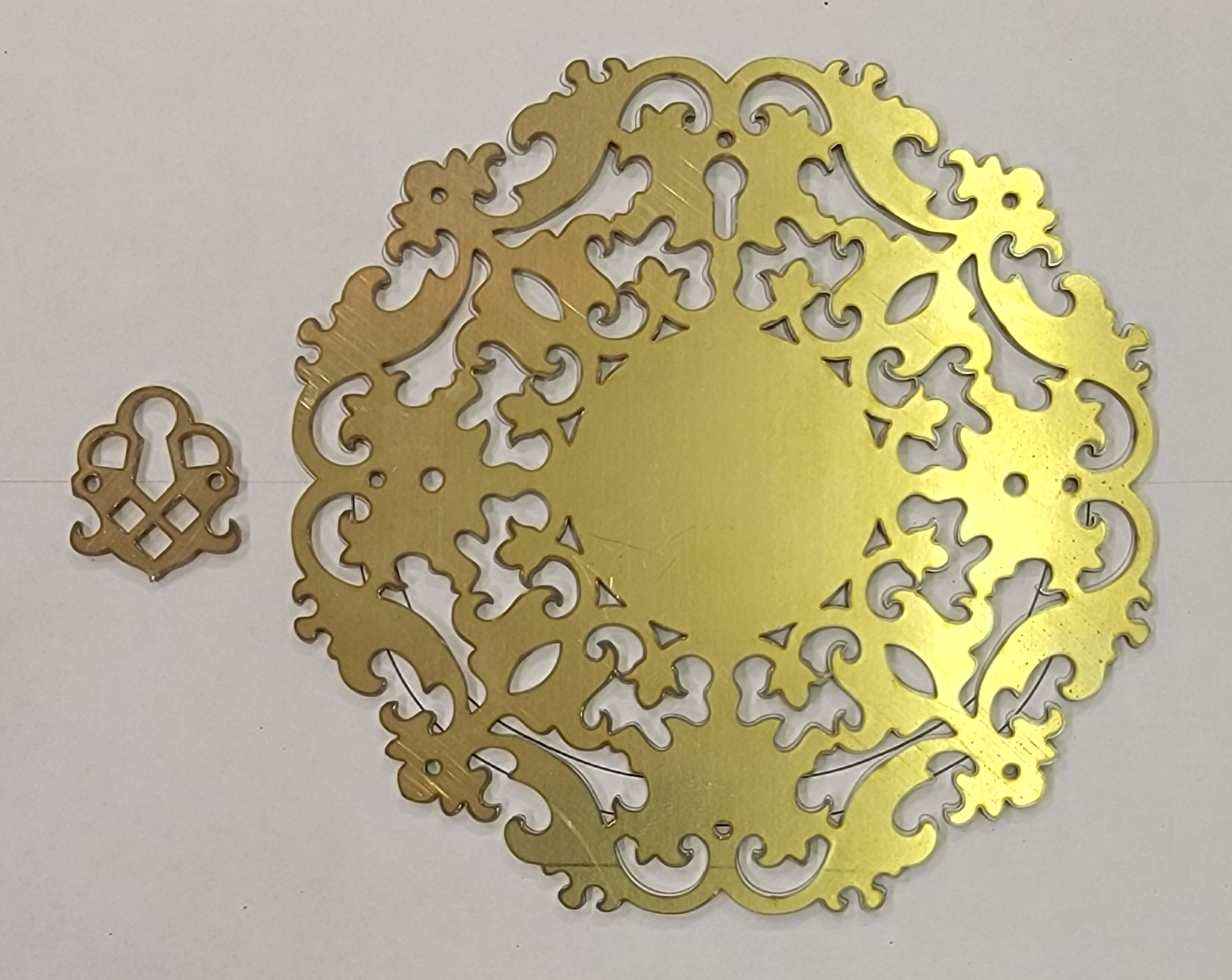

Historical images were analyzed in detail. Two photographs of him, taken by the firm of Kaufman and Fabry in 1923, survive as his 8×10 glass negatives, showing the most minute details, such as the distinctive brass drawer handles and keyhole escutcheon. I was able to examine the details. Because the furniture remained in the house, the Glessner family's daughter, Frances Glessner Lee, also had her five carved panels on the sideboard professionally photographed in 1936.

carved panels

The sideboard size was easily determined by using the oak wall panels as a guide and a set of original linen runners seen in a 1923 photograph still in the museum's collection. The size of the table was a little difficult. The size of the room was measured including a south-facing bay window built into the room to accommodate the table over its full length. To find out how much table space each guest should have (at least 24 inches), we measured the chairs and consulted our etiquette book. The final length of the table was determined to be 16 feet.

Schwebel table legs

The Schwebel family owns a Davenport dining room table with nearly identical legs and allowed Patrick to come to Peoria to take a closer look. David Martland, a major collector of Davenport furniture, invited Patrick to his homes in Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Through these visits, Patrick gained keen insight into how Davenport's sculptors executed their designs and constructed pieces such as the special hinges on the doors and the mortise-and-tenon joinery on the drawers. I got it.

Davenport's works in the Glessner House collection were also examined, including the partner's desk, which was found to have identical keyhole escutcheons in its drawers, and the fireplace surround in the main hall, which had similar egg-and-dart decorations to the sideboards. was also examined. His two headboards, made for the Glessner family's granddaughter and currently on display in the corner guest room, include one of his five sculptural designs on the sideboards, albeit on a larger scale. is depicted. Molds were made from some of Glessner's works for further study.

Patrick's mold making

Production began with the careful selection of quarter-sawn oak. This term refers to a specific method of cutting oak logs to maximize the beauty of the wood grain. This also produces distinctive pith rays throughout the grain, a unique feature of oak cut in this way. Scale drawings were created and a full-size mock-up was installed in the dining room to compare dimensions and proportions to historical photographs.

While two of Patrick's colleagues selected and cut the wood and assembled the furniture, Patrick concentrated on the intricate carvings. For every small detail, a virtually endless variety of chisels were used, each designed for a specific technique. The legs of his dining room table were initially modeled in clay until the exact contours of the acanthus leaves and feet were completed.

carving center panel

Decorative and structural hardware presented some of the most significant challenges. Some parts, such as handles and drawer pull posts, were cast using the lost-wax method, but it was prohibitively expensive for other parts, such as elaborate filigree backplates. These were hand cut after sourcing the brass to accurately reproduce the late 1990 colors.th Original of the century. Davenport's signature cast iron brackets, used to secure the table top to the apron, were cast in the foundry. Joan Parcher, a renowned jewelry designer and historic furniture hardware expert based in Providence, Rhode Island, was involved in this phase of the project.

brass hardware

Once all the pieces were complete, the table and sideboard were carefully wrapped and packed for the trip from Newton to Chicago. It took eight people to transport the sideboard into the house, using a specially constructed stand to hold the sideboard as it was carried up the front stairs.

moving sideboard

The sideboard was reset along with many of the parts that were visible in the 1923 photo. The new furniture and the identities of key donors were revealed on the evening of December 5, 2023, in front of an appreciative audience. The second event was held on February 6th.

Sideboard

The final stage of the project will include replicas of the missing side chairs. Patrick is hard at work on these chairs, which are scheduled for delivery in late September 2024. Once installed, the dining room will serve as a unique venue for hosting dinner parties of up to 18 people, just as the Glessner family did. A century ago.

For additional information and images, Glessner House has created two “Secret of Glessner House” videos available on YouTube.

Secret Part 44 – History and Design

Secret #45 – Furniture reproduction

table

For dining room rentals for special events, call 312-326-1480 or email info@glessnerhouse.org.