Many theater artists get excited when their shows are called “jukebox musicals,” in much the same way that literary novelists get excited when they're told they've written “beach books.” Even if it's still a form that audiences embrace, it's hard to get the jukebox musical taken seriously.

Some artists don't care. Broadway still does run-of-the-mill biographical musicals (most recently, Neil Diamond's A Beautiful Noise) or greatest hits compilations (Huey Lewis & the News' recent, tune-filled The Heart of Rock and Roll). Others take a more modern approach. Moulin Rouge is like a mixtape musical, with song selections from the original Baz Luhrmann film expanded (or bloated) for the Broadway stage. Or Spotify playlist musical &Juliet, which basically infuses your favorite '90s and 2000s pop songs with Shakespeare's story (and somehow it works).

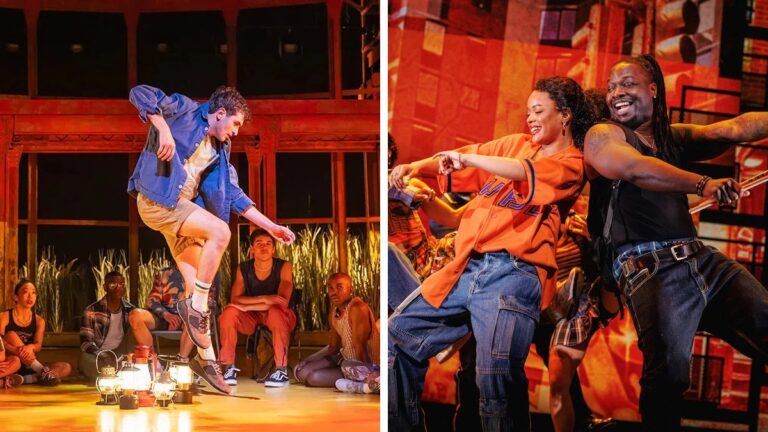

This season, two shows are aiming to do more than that, incorporating existing songs into new forms in original (or semi-original) ways. Justin Peck's “The Illinois” was nominated for four Tony Awards on Sunday, including best musical and best choreography for Peck. “Hell's Kitchen,” which features songs by Alicia Keys, was also nominated for best musical.

“Illinois” is Peck's take on Sufjan Stevens' 2005 album of the same name, a New York City Ballet star's take on the musical. So is it a jukebox musical? Surely only the saddest cafe in America would play these songs on its jukebox. And there's a tension with the word “musical” itself: Is a show with a band singing and dancers acting a musical?

Peck and Jackie Sibley Drury, who co-wrote the story, gave them more constraints than most, sticking with songs from a single album that has no plot of its own. You can tell they have a love for the source material — maybe too much. Instead of using the songs as a springboard, they've crafted a story that is often lyric-bound and nonsensical at best, and nonsensical at worst. To cram as many songs in as possible, the structure is a clumsy halve, with the first half dedicated to the writing group in a sort of Canterbury Tale in the Woods (which is as corny as it sounds), where dancers playing identifiable characters act out scenarios from the more outlandish songs in “Illinois.” It's unlikely anyone listening to Stevens's devastating “John Wayne Gacy Jr.” will identify with this story. We've all thought, “I'd love to see a dancer in a clown costume pretend to kill another dancer dressed as a child on stage one day.” Stevens' songs are not meant to be interpreted that way. What's great about his songs is that they use the right words and details to elevate emotion and connection to a higher level of thought. Sure, “John Wayne Gacy Jr.” is about a serial killer dressed as a clown, but it's about the fear we have of ourselves. Peck takes it from a higher level down to the details.

Sufjan Stevens, on the other hand, is not there. The biggest thing that makes this album more than a jukebox is that it doesn't try to emulate his distinctive vocal style. Instead, a trio of fine vocalists (Elijah Lyons, Shara Nova, and Tasha Viets-Van Leer) make the songs their own, in their own haunting and moving way. But the story is not so free-spirited, especially in the second half, when the protagonist, Henry (danced by Lissy Úbeda), comes into the woods in a baseball cap, T-shirt, and button-down shirt, looking just like… Sufjan Stevens. This creates a strange and unnecessary tension between fiction and (autobiographical?) biography.

Ultimately, Peck is too fixated on assembling a Frankenstein story around the songs, rather than respecting them enough to make them his own. The success of the show depends on the audience dismantling their previous associations with the songs, their sense of story and narrative, and focusing instead on the moment-to-moment emotions evoked by the dance.

If Sufjan Stevens is at the forefront on “Illinois,” Grammy Award winner Alicia Keys is front and center on “Hell's Kitchen.” do Some of the songs sound like they'd be on a jukebox, but again, it doesn't follow the usual jukebox formula. With music and lyrics by Keys and a book by Christopher Diaz, the musical is based on Keys' life, but not on an epic scale, focusing on a brief period in her life when she was 17 and living with her single mother in the Riverside Apartments, a public housing project for artists in New York City.

The story is not groundbreaking: Ali (in Maria Joy Moon's strong debut) falls for the wrong boy, but he might be the right boy. Ali's mother doesn't want her to fall in love too hard or too quickly. Ali and her mother have a falling out. Ali and her boyfriend, Nak, have sweet moments and misunderstandings. There's a tense altercation with the police. And Ali finds herself at the piano under the tutelage of a no-nonsense teacher who sings like Nina Simone.

What's interesting here is that Keys not only chose songs from her debut album, which she released when she was 20, but also from the past 20 years. This provides an interesting lens through which to consider her later work. Even when we're writing songs in our 20s, 30s and 40s, aren't we still writing about the emotions we felt in our teens? “Hell's Kitchen,” which received 13 nominations for Sunday's 77th Tony Awards, makes a strong case in the affirmative.

So “Hell's Kitchen” sells what “Illinois” lacked: personality. Thanks to the performances of the actors, the show thrives on pure personality, an outward interpretation of the personality power of Keys' songs.

Because Keys and Diaz decided not to place too much emphasis on the hits, there are some surprises: “Fallin',” the best-known song from Keys' debut, was given not to Ali but to his feuding, cheating parents, and is a jazzy reinterpretation that's a far cry from jukebox pastiche; “Empire State of Mind” is more of a coda than a climax; and the most impactful, and the one that gets the loudest applause, is the lesser-known “Perfect Way to Die,” given to Ali's music teacher as the first act closes (sung by the excellent Keysia Lewis).

As a result, the film feels less like a theatrical greatest-hits show and more like a sincere coming-of-age musical written with loving intimacy.

In fact, what most connects “Illinois” and “Hell's Kitchen” and sets them apart from their more robotic jukebox brethren is their honesty. Neither rests on the pleasure of listening to your favorite tunes; “Illinois” demands effort from you (there's a lot of reading in the program beforehand if you want to understand the story in a human way); “Hell's Kitchen,” on the other hand, depends on you remembering what it was like to be 17, whether you listened to Alicia Keys or not.